(This article originally appeared on Gantthead.com)

“The beginning is the most important part of the work.” Plato, Greek philosopher and writer, 429–347 B.C.E.

I’ve written several articles about a manager’s relationship with a team that has already formed. A manager’s relationship with a team as they work is essential for cultivating a self-organizing team and maintaining a link with the organization. But a managers role in growing effectives teams starts long before the work actually begins.

The 60-30-10 Principle

J. Richard Hackman, has been studying teams for decades. One of his most significant findings is that 60% of the variation in team effectiveness is attributable to the design of the team, 30% to the way the team is launched, and 10% to leader coaching once the team is underway. By “design of the team,” he doesn’t just mean picking the best people. You also have to think about the nature of the work, articulate a goal, and plan for enabling supports.

Aim for Flexible, Long-lived Teams

You can call a group of people a team the first day they come together. But that doesn’t mean they’ll achieve teamwork right away. People need time to understand each others strengths, weaknesses and work styles. They need to agree on, try, and adjust the way they work together to find their groove.

In many organizations, managers from cross-functional teams to meet the needs of a specific project. In some cases, that means the team will be together for a long time. More often, it means teams will be disbanded after a few weeks or months. That’s barely enough time for a team to gel and gain the benefit of the team effect.

Analyze the work that’s in the pipeline. Aim to organize the work so that teams have “whole” work–creating a product or service that has meaning from a business perspective. Look at the trade-offs and tensions inherent in the product. Make sure people who represent those aspects are part of the team. Look for dependencies and to the extent possible, keep them within a team boundary. Form teams that have the breadth of skills to handle a broad range of work.

Then, bring work to the teams, rather than reforming teams for each new project. You won’t find a team that’s perfect for all the work in the pipeline. When teams lack a specific expertise, keep the core team in tact and add expertise.

Articulate a Compelling Goal

An effective goal statement does two jobs. First, it focuses the attention and effort of the team. When the team has a shared understanding of what their task is, they pull in the same direction. When teams have don’t agree on the goal–or the goal is so vague it’s open to many interpretations–team members waste time and brain cycles arguing, working at cross purposes, or doing the wrong work.

Second, a well-formed goal engages the team in a meaningful challenge. An effective goal provides a sense of purpose to the teams work. The goal might be solving an important problem, enabling business, launching a new product, or meeting a customer need. State the goal in a way that taps into purpose.

Take the goal handed down to the FinCore team: “Maintain the FinCore Product.” That goal isn’t enough to get someone out of bed in the morning. It talks about a process (maintenance), but leaves out the purpose. It misses the opportunity to tap into pride-in-work. A more compelling goal might be:

Sustain the FinCore product by adding necessary functionality and ensuring the technical integrity of the code, so we can provide uninterrupted service to 40,000 customers.

Not all work is exciting and sexy, but all work should have a purpose. Making that clear will help people focus and engage.

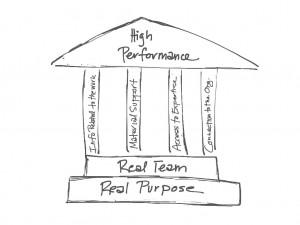

Pillars of support

The right people and a compelling goal are a good start. But if you neglect the pillars of support, the team may still wallow. The pillars of support are:

Information related to the situation, domain, problem and technology. These reinforce the goal, and provide the context for the team to make good decisions.

Material support, such as machines, tools, facilities, adequate budget, and supplies. Adequate material support communicates that the work of the team is important. Starving a team for resources undercuts the goal and creates cynicism. Paradoxically, providing too much isn’t good either. A certain level of constraint can drive creativity (and over constraint kills it).

Expertise to supplement the knowledge and skills of the team when needed. Even when the team has all the skills required by the task, they may need an expert eye for consulting or reviewing. Some times there is some aspect of the work that requires scarce knowledge. It may not make sense to develop that knowledge on the team, or it may only be needed for a short time.

Feedback loops that connect the team to the organization. Regular demos of working software allow the sponsor or product owner to see how the team is doing–and allows for course correction. The heartbeat of progress builds trust.

If any one of these pillars is missing, you’ve put the team at a disadvantage.

This Sounds Like More Work for the Manager. Why bother?

Team design is a pay me now, pay me later proposition. It’s a myth that you can throw a group of people together and they’ll gel as a team. Strong effective teams don’t just happen by some magic chemistry. Well designed teams are more resilient. They make better use of the knowledge, talents, and skills of team members. They function and stay on track with relatively little management intervention. You may not always be able to bring together the perfect team. But you can set a team up for success….or failure. It is up to you.

© derby for Insights You Can Use, 2011. |

Permalink |

No comment |

Add to

del.icio.us

Post tags: agile, management, organization design, teams

Feed enhanced by Better Feed from Ozh

![]()

![]()